If you’ve had a hysterectomy or are planning one, you want to know what to expect after the procedure, physically and emotionally.

Every woman’s experience is different. Women with painful conditions like endometriosis or pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) often experience complete relief of their symptoms after hysterectomy. Women who had pain with intercourse before surgery have also reported greater sexual satisfaction after hysterectomy.

For other women—especially those with reproductive cancers—having a hysterectomy can bring feelings of grief and loss. It’s common and normal to feel sad after a hysterectomy, especially if you wanted a child or more children. Tell your doctor if you’re feeling sad, anxious, or depressed, especially if these feelings aren’t getting better over time.

After a hysterectomy, it’s even more important to take care of your pelvic floor—the hammock-like system of muscles that holds your pelvic organs firmly in place. Removing your uterus can put you at greater risk of prolapse.

A prolapse is when an organ slips out of place and presses on another organ. A common example is when the bladder drops from its normal position and presses on the urethra. This can cause you to leak urine when you laugh, cough, or sneeze (stress urinary incontinence). Pelvic floor exercises, also known as Kegels, can help prevent bladder prolapse after hysterectomy.

We’ll talk more about how to protect your pelvic floor after a hysterectomy ahead.

Reasons for Hysterectomy

The most common reasons women have hysterectomies are endometriosis, fibroid tumors, and uterine prolapse. Some women elect to have a hysterectomy to treat severe pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), chronic pelvic pain, or endometriosis when all other treatments have failed.

Only around 10 percent of hysterectomies are performed to treat cancer (cervical, uterine, ovarian, or endometrial).

Types of Hysterectomies

There are different types of hysterectomy, and they can have very different outcomes, depending on which organs are removed.

- Partial hysterectomy: Also known as a subtotal or supracervical hysterectomy, only the uterus is removed. The cervix, fallopian tubes, and ovaries remain.

- Total hysterectomy: This procedure involves removing the uterus and cervix; the surgeon may also remove the fallopian tubes (salpingectomy) and/or the ovaries (oophorectomy), depending on the woman’s risk factor for cancer, or if cancer or precancerous cells are present. Removing the ovaries will trigger surgery-induced menopause.

- Radical hysterectomy: This procedure involves removing the uterus, ovaries, cervix, tissue on both sides of the cervix, and the upper part of the vagina. Radical hysterectomy is typically only used to treat more advanced cancers of the cervix.

Most hysterectomies today are minimally invasive, meaning they are performed through very small incisions and have a short recovery time (around 2 weeks). A smaller number of hysterectomies are abdominal, which involves a big belly incision and long recovery (around 6 weeks).

Hormonal Changes After Hysterectomy

The ovaries are the epicenter of estrogen and progesterone production. When the ovaries are removed during a hysterectomy it triggers what’s called “surgery-induced menopause.”

If only your uterus and cervix are removed (total hysterectomy) you might still experience a drop in hormone levels and have some menopausal symptoms, but usually to a much lesser extent.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) can relieve menopause symptoms if you have a significant drop in hormones after surgery. Menopause symptoms can include:

- Mood swings

- Hot flashes

- Night sweats

- Irritability

- Anxiety

- Vaginal thinning

- Vaginal dryness

- Lower sex drive

- Headaches

Physical Changes After Hysterectomy

Two common questions among women who have had a hysterectomy or plan to have one are:

- How do organs settle after hysterectomy? Although the uterus doesn’t typically take up much room in the pelvis, after a hysterectomy the remaining abdominal and pelvic organs will shift slightly to fill the space. Sometimes this shift can cause incontinence after hysterectomy and other problems. Keeping your pelvic floor muscles strong with regular exercise can help prevent this.

- How do the ovaries stay in place after hysterectomy? The ovaries are connected to the uterus by the fallopian tubes. They’re held in place by ligaments that extend from the upper part of the uterus to the lower part of the ovaries. If you’re having a hysterectomy but want to preserve your ovaries, your doctor can explain in detail how he or she will reattach the ovaries once they are separated from the uterus.

Pelvic Organ Prolapse After Hysterectomy

Women are at an increased risk for prolapse after hysterectomy. A prolapse occurs when an organ in the pelvis, such as the bladder, slips from its normal position. Pelvic pressure after hysterectomy is a symptom of a prolapsed organ.

To understand why prolapses happen it helps to know a bit about pelvic anatomy: The organs inside your pelvis are attached to the pelvic wall by ligaments, muscles, and tissues. When the cervix and uterus are detached from the vagina and removed from the body during a hysterectomy, the surgeon must then reattach the vagina to ligaments in the pelvis. This can leave it less secure and vulnerable to prolapse.

Types of prolapse that can happen after hysterectomy include:

- Vaginal vault prolapse: This is when the top section of the vagina collapses into the bottom section. In severe cases, the vagina turns “inside out” and can even protrude outside of the body. Vaginal prolapse after hysterectomy is fairly common, but only a relatively small percentage of women overall will experience this complication.1

- Cystocele: This is when the supportive tissue between the bladder and vaginal wall becomes weakened, allowing the bladder to bulge into the vagina.

- Rectocele: This is when the tissue that separates the rectum from the vagina weakens, creating a bulge against the back wall of the vagina.

- Enterocele: This is when the small intestine drops into the lower pelvic cavity and presses against the upper part of the vagina. Rectocele and enterocele sometimes occur together in women who have had their uterus removed.

All of this sounds really scary, we know, but it’s important to understand that having preexisting pelvic floor problems prior to surgery is the single greatest risk factor for prolapse.1

Women who didn’t have problems with prolapse prior to surgery are at a much lower risk of developing problems after surgery.

It’s also important to know that prolapse after a hysterectomy is more common in women who have had multiple children and already have weakened pelvic floor muscles.

Protecting Your Pelvic Floor After Hysterectomy

What can you do to prevent pelvic floor problems if you’ve had a hysterectomy? Being proactive is key. Follow these tips to protect your pelvic floor.

Get Constipation Under Control

Repeated straining from constipation or even a single episode of intense straining can damage your pelvic floor muscles. If you’re prone to constipation, use proper bowel emptying techniques, eat a high-fibre diet that promotes softer stools, and use gentle vegetable laxatives or an enema when needed to promote bowel movements. Talk to your doctor if you have persistent constipation.

Eat a Healthy Diet

A fibre-filled diet rich in fruits and vegetables, whole grains, nuts, and healthy proteins can help you manage your weight and stay regular. Avoid foods that cause abdominal bloating, constipation, or diarrhea, which can lead to straining on the toilet and make it difficult to pass wind; chronic straining can cause an organ to prolapse.

Manage Your Weight

Having good strength and muscle tone reduce your risk of straining your muscles from everyday activities (lifting, pulling, pushing, etc.). This in turn reduces your risk of prolapse and UI. Just be sure to avoid exercises that put too much pressure on your pelvic floor—activities like intense core exercises, extreme strength training, high-impact aerobics, and running, especially if you already have weak pelvic floor muscles.

Address Frequent/Chronic Cough

When you cough your abdominal muscles press down against your pelvis. A chronic cough can weaken your pelvic floor muscles and lead to prolapse. Talk to your doctor about how to manage chronic coughing. If you smoke, get help quitting.

Do Your Kegels!

Doing Kegel exercises after hysterectomy is one of the most important ways you can protect your pelvic floor, the hammock-like system of muscles that stretch across your pelvis. These muscles are part of your core and are vital for posture, intra-abdominal pressure, and pelvic organ support. Doing Kegels regularly will help you keep these muscles strong to prevent UI and prolapse.

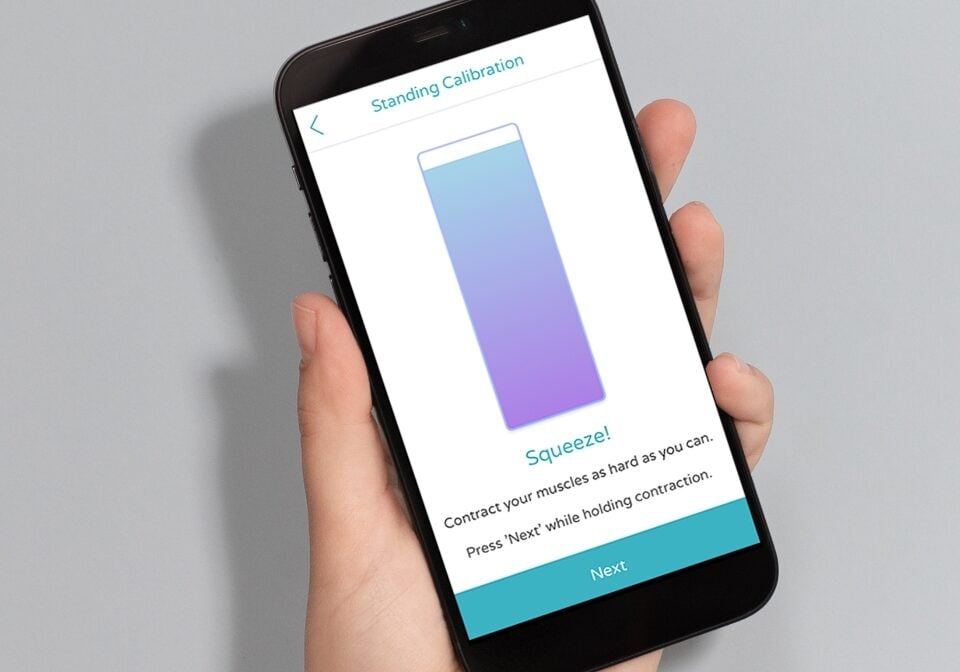

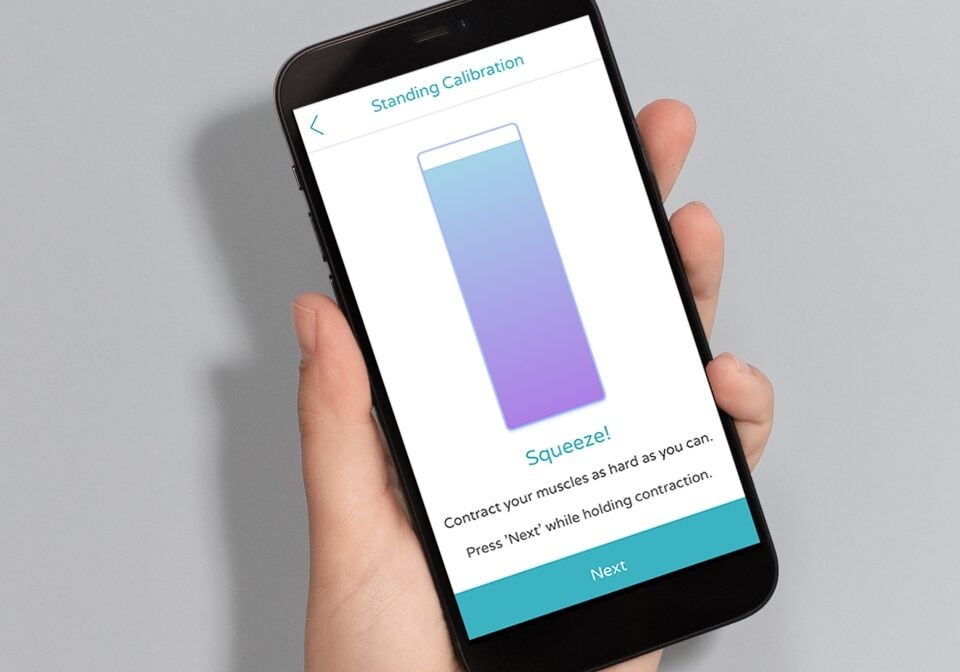

You might find it helpful to use a Kegel exerciser device like PeriCoach. Most women don’t perform Kegels correctly with written instructions alone, and this is where PeriCoach can really make a difference.

PeriCoach is a vaginally insertable biofeedback device fitted with sensors that detect when you squeeze against it. It’s been called one of the best pelvic floor trainers on the market today. PeriCoach pairs with your smartphone and guides you through pelvic floor exercise routines in real time!

Hear what women are saying and try it for yourself. Also, check out our guide on how to properly exercise your pelvic floor muscles.

Cheers to your good health, now and always.

Have a question?

We’re here to support you. We’ve answered your most common questions or you can contact us below.